viernes, octubre 05, 2012

@OLPL on confirms detention of Yoani Sanchez

jueves, octubre 04, 2012

Venezuela, Oct. 7: The possible, the probable, and the preferable

HAVANA TIMES — It's been 14 years since Hugo Chavez burst into the Venezuelan presidency, and with him his project known as the "Bolivarian Revolution."

Weariness with the corruption of the Fourth Republic and the exclusion of the poor (who were suffering the impact of neoliberal policies) led to the establishment of an electoral front that put forward the lieutenant colonel, who won by a large margin over the other candidates, especially the representatives of the traditional parties.

From that moment on, the new government faced stiff resistance from those parties, as well as from an alliance of the media and the urban middle and upper classes, which in 2002 and 2003 turned to strategies of destabilization, including a failed coup. The new government managed to weather the storm, reconstructing a framework of domestic and international legitimacy in successive elections from 2004 to 2006.

The process, in an attempt to overcome the deficits of the Fourth Republic, expanded citizens' participation in Venezuela and put the social agenda in the center of the debate. Public policies grew, generating processes for including the marginalized – thanks to revenues generated by oil.

These elements — certainly positive — joined the redefinition of the regulatory framework (with a new constitution and the passage of new laws) with the recuperation of the role of the state as an active agent in national life, as it delineated the main features of the project that was (self) identified as Bolivarian.

But the democratizing effect of the new government was gradually tinged, starting in 2006, by increasing personal ambitions and political bureaucratization with the emergence of a hyper-presidential regime, a dominant political organization (the United Socialist Party of Venezuela, or PSUV), and the development of participatory mechanisms (community councils) that operated as instruments of political control and mobilization.

The rise of Hugo Chavez's charismatic leadership was accompanied by the discretionary use of state resources, as well as by the usurpation of the other national powers, both in party politics and social forces (movements, organizations) and the media, including those identified with the bourgeoisie as well as by popular figures and the independent left.

With the spreading of the idea of "Socialism of the 21st Century," the promotion of new enabling legislation, the proposal for constitutional reform and the creation of the PSUV, these steps advanced the authoritarian and statist tendencies, which were particularly visible in government institutions, the economic model and the legal architecture of the nation.

The concentration of power, which converges in the figure of President Hugo Chavez, appeals to a leader-masses relationship and confrontation with the enemy (opponents) in a strategy that tends to increasingly ignore current political norms — including the constitution itself — and which involves the manipulation of justice, control and surveillance of the press, and setbacks with respect to the human rights situation.

Likewise, within the Bolivarian ranks themselves, restrictions have been placed on the options for dissent and participation in the construction of the process; instead, there are constant appeals to the commander-president, to a military lexicon (using words like "battle," "campaign" and "missions"), and reliance on command and control styles implemented within the vertical structure of Chavez that leave no room for such "bourgeois folly."

Fidel Castro and Hugo Chavez. Foto: Cubadebate.cu, March 2012.

With such a backdrop, Venezuela finds itself heading for the upcoming October 7 elections, one of the most significant moments of contemporary political history. On one side, this will reveal all of the strengthening and wearing down of a government anchored in power for 14 years, one whose success depends largely on the charismatic leadership of Hugo Chavez and the scope of his successful (yet deteriorated) social policies.

In the opposite corner, a motley opposition seems to have overcome its errors and divisions and has projected the youthful figure of Henrique Capriles, speaking in less belligerent language than his opponent but sharing the rosary of promises, magical-religious allusions and a not always well outlined program.

Both options seem not to have convinced an important segment of the electorate (the "neither-nors"), those who vacillate between recognition of the positive social management of the Chavez government and opposition to his authoritarian manner; they swing between hope for change and distrust of the old elites who surround the opposition candidate.

The underlying drama, however, is that the large blocs competing in the current electoral conjuncture — the Chavistas vs. the anti-Chavistas — are appealing to similar organizational and identifying elements: parties with diffuse ideologies, charismatic leadership, the use of rhetoric; and populist, patronage-fueled mobilizing programs and styles.

A depolarizing option (combining the defense of rights and freedoms with a sincere and substantive concern for social justice) has been obstructed by the polarized atmosphere as well as the institutional design (see the "Organic Law on Electoral Process") that favors and perpetuates it.

Experiences like the "Partido Patria para Todos" party, in 2010, and the bloc of popular organizations that proposed labor leader Orlando Chirino as an independent candidate — against the officialist ruling party and the opposition — don't seem to have many options in the current scenario, even when their presence is hopeful for those of us who identify with a socialist and democratic option as a solution to the crisis in Venezuela.

Once again, the relationship between the possible, the probable and the preferable is straining the panorama of political analyses and options. This explains why in the upcoming presidential election, the gaze of more than a few democrats and social activists is focused on preventing the victory of Chavez, whose victory — if we consider the sustained and belligerent references of his performance and speech — threatens to radically capture and transform the political arena, negating the possibility of representing political plurality and a correlation of forces and eliminating the autonomous action of citizens.

This is an interpretation accompanied by the realization that even if Capriles wins, he would have to incorporate those popularly recognized policies of the current government — social missions and community participation — and govern with a style and program of national (re)conciliation, in light of the enormous heterogeneity of the alliance around his candidacy and in the face of Chavez's political strength, which would be converted into (unless an electoral defeat or the death of their leader plays out adversely) a formidable and united opposition.

Unlike in other nations of the hemisphere, what's at stake in Venezuela isn't a simple rotation within the ruling elite or some moderate shift in the continuity of a political and economic project of integration into the system of globalization.

The central dilemma of every Venezuelan is whether they will again cast their vote (and their trust) in a government that threatens to radically and irreversibly alter the political field with the advancement of its authoritarian tendencies, or whether they will choose an alternative — with its inconsistencies and weaknesses — that objectively would have to negotiate with its opponents and the rest of society to lay better foundations for the exercise of citizens' rights and autonomy and political pluralism.

Because of that, many people won't vote so much for Capriles and his electoral alliance/program as they will against Chavez and his visible hegemonic project. Whatever the result of the October 7th elections (the change of a regime or the deepening of an authoritarian course), the fact is that a new stage begins in Venezuela of increasing complexity and political risks.

Tonight in Miami, USA: U.S. Cuba Policy and the Cuban-American

miércoles, octubre 03, 2012

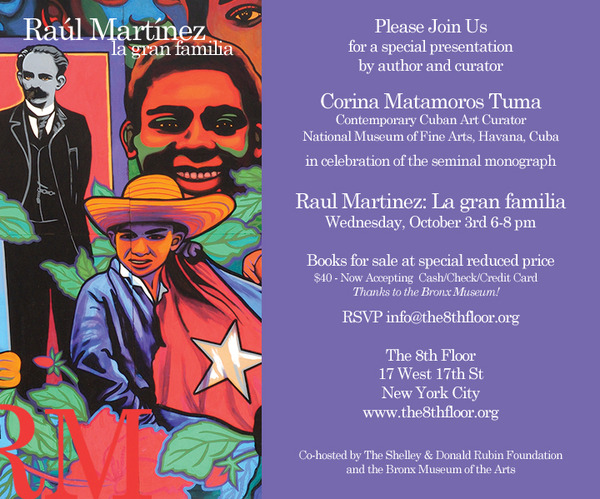

La Gran Familia: TONIGHT Corina Matamoros on Raúl Martínez

|  |  |

Please Join Us

for a special presentation by author and curator

Corina Matamoros Tuma

Contemporary Cuban Art Curator

National Museum of Fine Arts, Havana, Cuba

in celebration of the seminal monograph

Raul Martinez: La gran familia

Wednesday, October 3rd 6-8 pm

Lecture 6:30 Reception to follow

Books for sale at special reduced price $40

All payments accepted, administered by the Bronx Museum

RSVP info@the8thfloor.org

The 8th Floor

17 West 17th St

New York City

www.the8thfloor.org

Co-hosted by The Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation and the Bronx Museum of the Arts