HAVANA TIMES — It's been 14 years since Hugo Chavez burst into the Venezuelan presidency, and with him his project known as the "Bolivarian Revolution."

Weariness with the corruption of the Fourth Republic and the exclusion of the poor (who were suffering the impact of neoliberal policies) led to the establishment of an electoral front that put forward the lieutenant colonel, who won by a large margin over the other candidates, especially the representatives of the traditional parties.

From that moment on, the new government faced stiff resistance from those parties, as well as from an alliance of the media and the urban middle and upper classes, which in 2002 and 2003 turned to strategies of destabilization, including a failed coup. The new government managed to weather the storm, reconstructing a framework of domestic and international legitimacy in successive elections from 2004 to 2006.

The process, in an attempt to overcome the deficits of the Fourth Republic, expanded citizens' participation in Venezuela and put the social agenda in the center of the debate. Public policies grew, generating processes for including the marginalized – thanks to revenues generated by oil.

These elements — certainly positive — joined the redefinition of the regulatory framework (with a new constitution and the passage of new laws) with the recuperation of the role of the state as an active agent in national life, as it delineated the main features of the project that was (self) identified as Bolivarian.

But the democratizing effect of the new government was gradually tinged, starting in 2006, by increasing personal ambitions and political bureaucratization with the emergence of a hyper-presidential regime, a dominant political organization (the United Socialist Party of Venezuela, or PSUV), and the development of participatory mechanisms (community councils) that operated as instruments of political control and mobilization.

The rise of Hugo Chavez's charismatic leadership was accompanied by the discretionary use of state resources, as well as by the usurpation of the other national powers, both in party politics and social forces (movements, organizations) and the media, including those identified with the bourgeoisie as well as by popular figures and the independent left.

With the spreading of the idea of "Socialism of the 21st Century," the promotion of new enabling legislation, the proposal for constitutional reform and the creation of the PSUV, these steps advanced the authoritarian and statist tendencies, which were particularly visible in government institutions, the economic model and the legal architecture of the nation.

The concentration of power, which converges in the figure of President Hugo Chavez, appeals to a leader-masses relationship and confrontation with the enemy (opponents) in a strategy that tends to increasingly ignore current political norms — including the constitution itself — and which involves the manipulation of justice, control and surveillance of the press, and setbacks with respect to the human rights situation.

Likewise, within the Bolivarian ranks themselves, restrictions have been placed on the options for dissent and participation in the construction of the process; instead, there are constant appeals to the commander-president, to a military lexicon (using words like "battle," "campaign" and "missions"), and reliance on command and control styles implemented within the vertical structure of Chavez that leave no room for such "bourgeois folly."

Fidel Castro and Hugo Chavez. Foto: Cubadebate.cu, March 2012.

With such a backdrop, Venezuela finds itself heading for the upcoming October 7 elections, one of the most significant moments of contemporary political history. On one side, this will reveal all of the strengthening and wearing down of a government anchored in power for 14 years, one whose success depends largely on the charismatic leadership of Hugo Chavez and the scope of his successful (yet deteriorated) social policies.

In the opposite corner, a motley opposition seems to have overcome its errors and divisions and has projected the youthful figure of Henrique Capriles, speaking in less belligerent language than his opponent but sharing the rosary of promises, magical-religious allusions and a not always well outlined program.

Both options seem not to have convinced an important segment of the electorate (the "neither-nors"), those who vacillate between recognition of the positive social management of the Chavez government and opposition to his authoritarian manner; they swing between hope for change and distrust of the old elites who surround the opposition candidate.

The underlying drama, however, is that the large blocs competing in the current electoral conjuncture — the Chavistas vs. the anti-Chavistas — are appealing to similar organizational and identifying elements: parties with diffuse ideologies, charismatic leadership, the use of rhetoric; and populist, patronage-fueled mobilizing programs and styles.

A depolarizing option (combining the defense of rights and freedoms with a sincere and substantive concern for social justice) has been obstructed by the polarized atmosphere as well as the institutional design (see the "Organic Law on Electoral Process") that favors and perpetuates it.

Experiences like the "Partido Patria para Todos" party, in 2010, and the bloc of popular organizations that proposed labor leader Orlando Chirino as an independent candidate — against the officialist ruling party and the opposition — don't seem to have many options in the current scenario, even when their presence is hopeful for those of us who identify with a socialist and democratic option as a solution to the crisis in Venezuela.

Once again, the relationship between the possible, the probable and the preferable is straining the panorama of political analyses and options. This explains why in the upcoming presidential election, the gaze of more than a few democrats and social activists is focused on preventing the victory of Chavez, whose victory — if we consider the sustained and belligerent references of his performance and speech — threatens to radically capture and transform the political arena, negating the possibility of representing political plurality and a correlation of forces and eliminating the autonomous action of citizens.

This is an interpretation accompanied by the realization that even if Capriles wins, he would have to incorporate those popularly recognized policies of the current government — social missions and community participation — and govern with a style and program of national (re)conciliation, in light of the enormous heterogeneity of the alliance around his candidacy and in the face of Chavez's political strength, which would be converted into (unless an electoral defeat or the death of their leader plays out adversely) a formidable and united opposition.

Unlike in other nations of the hemisphere, what's at stake in Venezuela isn't a simple rotation within the ruling elite or some moderate shift in the continuity of a political and economic project of integration into the system of globalization.

The central dilemma of every Venezuelan is whether they will again cast their vote (and their trust) in a government that threatens to radically and irreversibly alter the political field with the advancement of its authoritarian tendencies, or whether they will choose an alternative — with its inconsistencies and weaknesses — that objectively would have to negotiate with its opponents and the rest of society to lay better foundations for the exercise of citizens' rights and autonomy and political pluralism.

Because of that, many people won't vote so much for Capriles and his electoral alliance/program as they will against Chavez and his visible hegemonic project. Whatever the result of the October 7th elections (the change of a regime or the deepening of an authoritarian course), the fact is that a new stage begins in Venezuela of increasing complexity and political risks.

jueves, octubre 04, 2012

Venezuela, Oct. 7: The possible, the probable, and the preferable

Crucial Elections in Venezuela October 4, 2012

By Armando Chaguaceda

Tonight in Miami, USA: U.S. Cuba Policy and the Cuban-American

The Center for International Policy in collaboration with the Department of Global and Sociocultural Studies, Florida International University (FIU) & the Greater Miami Chapter of the ACLU

Invite you to a discussion of

U.S. Cuba Policy and the Cuban-American

Thursday, October 4, 2012

4:00 - 7:30 p.m.

Tower Theater

1508 S.W. 8th Street

Miami, Florida

Recent U.S. regulations have allowed for unlimited Cuban-American travel and remittances to Cuba and increased "purposeful" travel by other citizens.

In two panels we will explore the effect of this opening in Miami and Cuba and examine how Florida voting influences U.S. Cuba policy and how it is likely to do so in the future.

Wine and Cheese

4:00 - 4:45 p.m.

Performance by Yrak of Doble FILO Cuba hip-hop band

4:45 - 5:00 p.m.

(Courtesy of Miami Light Project)

Panel One - U.S.-Cuba Engagement

5:00 - 6:00 p.m.

Tessie Aral, President, ABC Charters

Alejandro Barreras and Arturo Lopez-Levy, CAFE (Cuban Americans for Engagement)

John De Leon, President, Miami ACLU

Lillian Manzor, Director, Cuban Theater Digital Archive, Assoc. Professor of Modern Languages & Literatures, University of Miami

Moderator: Silvia Wilhelm, President, CubaPuentes, Inc.

Panel Two - U.S. Policy and the Vote

6:00 - 7:00 p.m.

Freddy Balsera, Managing Partner, Balsera Communications

Alvaro F. Fernandez, Miami Progressive Project

Guillermo J. Grenier, Professor, Dept. of Global and Sociocultural Studies, FIU

Wayne Smith, Director, Cuba Project, Center for International Policy

Moderator: Wayne Smith

miércoles, octubre 03, 2012

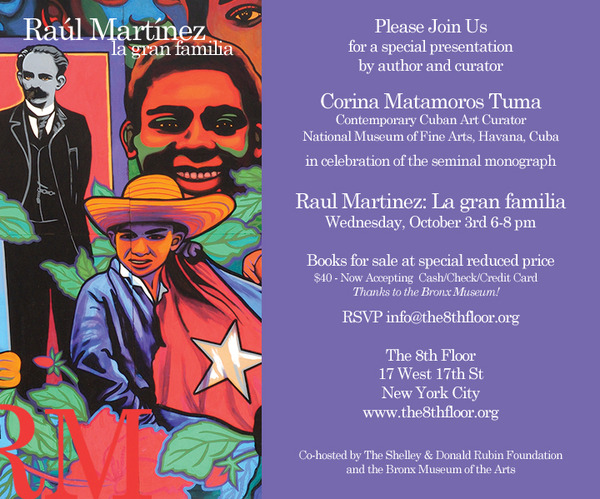

La Gran Familia: TONIGHT Corina Matamoros on Raúl Martínez

Guess who will be on hand to interpret for this event at The 8th Floor tonight? Yours truly. A little Cuban culture before the first presidential debate!!

|  |  |

Please Join Us

for a special presentation by author and curator

Corina Matamoros Tuma

Contemporary Cuban Art Curator

National Museum of Fine Arts, Havana, Cuba

in celebration of the seminal monograph

Raul Martinez: La gran familia

Wednesday, October 3rd 6-8 pm

Lecture 6:30 Reception to follow

Books for sale at special reduced price $40

All payments accepted, administered by the Bronx Museum

RSVP info@the8thfloor.org

The 8th Floor

17 West 17th St

New York City

www.the8thfloor.org

Co-hosted by The Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation and the Bronx Museum of the Arts

lunes, septiembre 17, 2012

Cuba, Miami y la homofobia

De izquierda a derecha: Jafari Sinclair Allen, Achy Obejas, Mabel Cuesta, Emilio Bejel y María Werlau. Arriba en la pantalla (y presentes en vivo por teléfono): Leannes Imbert e Ignacio Estrada.

Hoy leí en PD un resumen del panel sobre LGBT del sábado pasado en el NYPL de Harlem (vea mi foto de los ponentes arriba). Acerca de lo que Alexis Romay escribe allí sobre mi pregunta acerca de la homofobia en Miami hacia el final del evento, le digo: o me entendió mal o no me quisó entender. A eso regreso mas abajo.

Me alegro mucho de que alguien con su talento y sentido de matices y complejidades se haya tomado el tiempo de compartir con un público mas amplio lo que allí se discutió. A mi juicio, su resumen del evento está muy bien hecho y es bastante acertado - especialmente lo que escribe sobre cuan buena, honesta y llena de experiencias y hechos reales estuvo la intervención de la escritora Achy Obejas. Ella combinó una reflexión personal con citas muy específicas de leyes abusivas y violaciones claras de los derechos de la comunidad LGBT en Cuba por parte del gobierno.

También, las criticas abiertas de Achy a los métodos cínicos y paternalistas de Mariela Castro (a quien denominó "the fag-hag-in-chief") fueron contundentes e importantes. Al mismo tiempo, ella misma reconoció que Mariela - desde una posición de poder y privilegio - ha dado pasos positivos a favor de que haya mas tolerancia hacia la comunidad LGBT - especialmente para tratar de concienciar un poco a los hetero-retrógrados dentro de los círculos mas altos de poder en Cuba.

Hacía falta hacer un buen resumen del evento - porque fue poderoso y trató de un asunto importante. Además, sabemos que es un asunto que ha sido manipulado por el gobierno cubano y por intereses políticos.

Como bien dice Alexis, fue una pena que tantas de las personas presentes en la intervención de Mariela Castro de hace tres meses en el NYPL no se tomaran el tiempo de escuchar a las otras muchas voces que estuvieron presentes el sábado - tanto cubanos activistas desde la isla y escritores del exilio, como académicos como Jafari Allen, que ha dedicado bastante de su carrera a este tema.

Me hubiera gustado mucho presenciar un debate abierto y respetuoso entre personas que abogan por los derechos de la comunidad LGBT, pero desde posicionamientos políticos distintos. Achy y Mariela; Yoani y La Negra Cubana Tenía que Ser; Paquito "el de Cuba" y Paquito “el d'Rivera”; Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo y Yasmín Portales Machado; Julio Cesar González Pages y hasta el mismísimo Miguel Barnet.

Pero ésto no pudo ser - ni en LASA, ni en la NYPL de la 42, ni en la de la 135. Parece que en el segundo caso Mariela no quería un debate de verdad sino solo un auditorio, y que ir hasta la calle 135 en un sábado tan bello era pedir demasiado a aquellos que quieren creer en una sola realidad luminosa "dentro" de la revolución.

No escuché a Mariela en Nueva York, pero sí la pude oir en LASA. La encontré bastante profesional, inteligente y conocedora a fondo de su tema. Pero al mismo tiempo había una gran laguna en su ponencia sobre la falta total de derechos de asociación independiente en Cuba para grupos LGBT. Es mas - y como bien dice Alexis - o estás con CENESEX, o no existes. Los activistas LGBT independientes son tratados como opositores y disidentes por definición, por el mero hecho de insistir en preservar su independencia.

Acerca de lo que escribió Alexis sobre Allen y sobre mi, solo le puedo decir - como digo arriba - , o nos entendió mal o no nos quiso entender. Allen es un experto en temas LGBT y acaba de publicar un libro titulado ¡Venceremos? (fíjense bien en el signo de interrogación) basado en sus investigaciones dentro de la isla. No lo he leído todavia, pero este resumen del contenido deja claro que nadie engañó a Allen durante su estancia en la isla:

"Promoting the revolutionary socialist project of equality and dignity for all, the slogan ¡Venceremos! (We shall overcome!) appears throughout Cuba, everywhere from newspapers to school murals to nightclubs. Yet the accomplishments of the Cuban state are belied by the marginalization of blacks, the prejudice against sexual minorities, and gender inequities."Es verdad que hacia el final del evento hice una pregunta a los ponentes pidiéndoles que compararan – según sus experiencias personales y estudios sobre el tema - la homofobia en Cuba con la de Miami. En mi pregunta nunca mencioné ni al gobierno cubano ni al norteamericano. Mi pregunta tenía la intención - después de oír bastante sobre los abusos gubermentales mas que condenables contra los gays en Cuba - de pedir a los ponentes que hablaran un poco sobre la homofobia por parte del pueblo cubano tanto dentro como fuera de la isla.

La homofobia tiene dos caras en todas las sociedades: la que se expresa a traves de las políticas gubernamentales y los derechos sociales según la legislación (o la falta de ellos); y la que se encuentra dentro de una cultura y de los corazones y las mentes de las personas.

Que culpa tengo yo - como canta Albita - que algunas de las personas presentes - como Alexis y la señora indignada que menciona - no me dieran el beneficio de la duda, y concluyeran que yo quería igualar discriminaciones sancionadas por un estado con los prejuicios que todos llevamos adentro?

Le doy gracias los ponentes por responder a mi pregunta honesta con respuestas tan serias y complejas como detalladas e íntimas. ¡Que siga el debate!

domingo, septiembre 09, 2012

LGBT Lives in Contemporary Cuba

LGBT Lives in Contemporary Cuba at the Schomburg Center, Sat, Sep 15, 3 pm

I don't expect Mariela Castro to be in attendance for this event but she should return to NYC just for it. She could contribute a bit and, I'm sure, learn a lot too.

It's really a fabulous set of smart people.

Be sure to RSVP. See you there!

Although Cuba has made major advances in LGBT rights in recent years, homophobia remains a problematic human rights issue.

A panel of scholars, writers, and activists, featuring Jafari Allen, Emilio Bejel, Mabel Cuesta, Ignacio Estrada, Leannes Imbert, and Achy Obejas, will discuss continuing challenges.

***

Jafari Sinclaire Allen (Ph.D., Columbia) is Assistant Professor of Anthropology and African American Studies at Yale University. Professor Allen works at the intersections of queer sexuality, gender and blackness. A recipient of fellowships from the National Science Foundation, Social Science Research Council Sexuality Research Program, and Rockefeller Foundation [Diasporic Racisms Project]; he teaches courses on the cultural politics of race, sexuality and gender in Black diasporas; Black feminist and queer theory; critical cultural studies; ethnographic methodology and writing; subjectivity, consciousness and resistance; Cuba and the Caribbean. Dr. Allen is the author of the critical ethnography, ¡Venceremos?: The Erotics of Black Self-Making in Cuba [Perverse Modernities series of Duke University Press, Fall 2011], and editor of Black/Queer/Diaspora– a special issue of GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies.

Emilio Bejel, poet, critic, and narrator, was born in Cuba, and has lived in the United States since the 1960s. He received his Ph.D. in Spanish and Spanish American literature from Florida State University (Tallahassee). In 1997 he was a member of the jury for the Casa de las Américas Literary Prize. He has published several books of literary and cultural criticism, among them Gay Cuban Nation, as well as several poetry collections. He has also published three versions of an autobiographical narrative: The Write Way Home. A Cuban-American Story (translated into English by Professor Stephen Clark), El horizonte de mi Piel (in Spanish), and O Horizonte da Minha Pele (in Portuguese). His latest scholarly book, José Martí: Images of Memory and Mourning, has been released by Palgrave Macmillan in September, 2012.

Mabel Cuesta is a Cuban born essayist and writer. Her education was completed amongst University of Havana (Cuba), University Complutense of Madrid (Spain) and The Graduate Center, City University of New York (United States). Cuesta has also dedicated a big deal of her professional career to teaching Latin American Literature, Literary Theory and Spanish Language. Her research focuses on Spanish Caribbean female authors, both in their homelands and abroad as well as in LGBT topics. She has published several peer reviewed articles in Cuba, United States, Canada, Brazil, Honduras, Colombia, Spain and Mexico. She is currently an Assistant Professor of US Latino/a and Caribbean Literatures at the Hispanic Studies Department of University of Houston.

Ignacio Estrada Cepero is the Executive Director of the Cuban Alliance Against AIDS.

Leannes Imbert Acosta is an independent journalist with CUBANET and holds a degree in Special Education. In 2007 she founded the Cuban Movement for Homosexual Liberation (MCLH), which became the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Rights Observatory (LGBT OBCUD). Leading this organization, she has conducted campaigns to demand and promote the right to freedom of sexual orientation and the civil rights of the LGBT people. She organized the first Gay Pride March held in Cuba in 2011, the first "Coming Out" march, and founded, together with other LGBT and Human Rights activists, the Cuban LGBT Platform (LGBT PLAC). Despite strong repression from the Cuban government, she continues many projects such as: a critical investigation of UMAP (Military Units to Aid Production, created in Cuba in the early 1960s), and the Truth and Memory project, aimed at exposing the crimes and abuses that have been perpetrated against LGBT people in Cuba over the past 50 years.

Achy Obejas is the author of the critically acclaimed novels Ruins (Akashic Books, 2009), Days of Awe (Random House, 2001) and two other books of fiction. Her poetry chapbook, This is What Happened in Our Other Life (A Midsummer Night's Press, 2007), was both a critical favorite and a best-seller. She edited and translated, into English, Havana Noir (Akashic Books, 2007), a collection of crime stories by Cuban writers on and off the island. Her translation, into Spanish, of Junot Díaz' The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (Riverhead, 2009)/ La Breve y Maravillosa Vida de Óscar Wao (Vintage/Mondadori) was a finalist for Spain's Esther Benítez Translation Prize from the national translator's association. She is a member of the Editorial Board of In These Times, the editorial advisory board of the Great Books Foundation, and a blogger for WBEZ.org.

Initial funding of the LGBT initiative provided by Time Warner Inc., with additional support from M.A.C. AIDS Fund, Arcus Foundation, and Friends of the LGBT Initiative.

Suscribirse a:

Entradas (Atom)